Docker Swarm: 10 Stupid Questions

Introduction

One of the main reasons I created my Raspberry Pi cluster was to investigate Docker Swarm in more detail. There are quite a few good articles out there that tell you how to set up Swarm, including some very good articles by Hypriot which were my original inspiration. However, as I’ve been experimenting with Swarm I’ve started asking myself some questions that these articles generally don’t answer. I’d like to share what I’ve found here. So, in no particular order, let the questions begin.

1: What on earth is Docker Swarm?

The Docker glossary defines Swarm as follows (emphasis is my own):

Swarm is a native clustering tool for Docker. Swarm pools together several Docker hosts and exposes them as a single virtual Docker host. It serves the standard Docker API, so any tool that already works with Docker can now transparently scale up to multiple hosts.

OK, so Swarm is a way of creating something called a cluster in such a way that whatever is in that cluster looks to the outside world like a single entity. So far, so good.

2: What on earth is a Cluster?

Let’s take a step back. According to Docker (once again, emphasis my own):

Clusters are groups of nodes of the same type and from the same cloud provider. Node clusters allow you to scale the infrastructure by provisioning more nodes with a drag of a slider.

Hmmm, not quite so helpful but this definition was taken from the introduction to Docker Cloud so it’s slightly biased. Perhaps a better definition that I’ve put together from several different sources is:

A cluster consists of one or more node instances, together with a service discovery endpoint which provides a unified view into the cluster.

Great.

3: What on earth is a Node?

Once again, from Docker:

A node is an individual host used to deploy and run your applications. … . Your hosts can come from several different sources, including physical servers, virtual machines or cloud providers.

OK, now I feel like I’m getting somewhere. Basically, a node is something that runs all the services necessary to support Docker containers. However, even this definition is somewhat open to interpretation. I use a Mac for my development. This machine has Docker Machine installed on it. Docker Machine is:

…a tool that lets you install Docker Engine on virtual hosts, and manage the hosts with docker-machine commands. You can use Machine to create Docker hosts on your local Mac or Windows box, on your company network, in your data center, or on cloud providers like AWS or Digital Ocean.

Just to make things complete, Docker Engine is what most people mean when they say “Docker”. It is the application that accepts docker commands from the command line interface. The point I’m making here is that even though my Mac can be thought of as being able to deploy and run containerised applications it is not, iteslf, a node. The virtual machines created using Docker Machine are the nodes. I can create one or more nodes on my Mac, just as I can create one or more nodes on a Linux server. Thus, clusters may comprised as follows:

- a single physical server running a single node (although there’s not much point in making this a cluster)

- a single physical server running multiple nodes

- multiple physical servers running a single node

- multiple physical servers running multiple nodes

4: What on earth is a Service Discovery Endpoint

Docker defines this as follows:

The Swarm managers and nodes use [the Service Discovery Endpoint] to authenticate themselves as members of the cluster. The Swarm managers also use this information to identify which nodes are available to run containers.

In order to work, Swarm requires a service discovery endpoint. Swarm supports multiple discovery backends. Typically, a hosted discovery service is used with Docker Swarm. This service maintains a list of IPs in the cluster. It is possible to use Docker Hub’s hosted discovery service with Swarm in development mode provided your nodes are connected to the public internet but this is not intended for production use. For live use, however, you want to use something like Consul which you can host on your own infrastructure.

So, whilst it would appear that Docker Swarm is a self-contained entity this is not, in fact, the case prior to Docker version 1.12. However, in version 1.12 Docker introduced Swarm Mode which runs its own internal DNS service to route services by name. Docker 1.12 still has a service discovery backend, it’s just internal. Swarm manager nodes assign each service in the swarm a unique DNS name and load balances the running containers. It is now possible to query every container running in the swarm through a DNS server embedded in that swarm.

5: Remind me again, what is Docker Swarm?

Essentially, Swarm allows multiple nodes to unite into a cluster with single management tier. It is basically master – slave system which orchestrates multiple containers in order to maintain a particular desired state. In order to do this, a docker service feature has been created as an extension of docker run. Whereas docker run creates an individual container the docker service create command creates a service which can run in one or more containers while the state of this service is maintained in the cluster using a raft consensus protocol.

6: A Raft Consensus Protocol, you say?

Swarm is used to run a service on multiple nodes. Each copy of this service must reflect the same desired state, for reasons that will become clear later (honestly!). In order to do this, Swarm implements the concept of desired state reconciliation using a raft consensus protocol. This explains what a raft consensus protocol is far better than I could, so I suggest you look at it (it’s a nifty animation) before reading further.

In essence what this means is that whenever there is a problem with the service running in any node in the cluster the swarm will recognise that there has been deviation from the desired state and will create a new container instance compensate. In order to do this it requires one or more of the nodes in the cluster to be defined as a manager node.

7: What’s a Manager Node?

I’ll let Docker speak for itself:

To deploy your application to a swarm, you submit a service definition to a manager node. The manager node dispatches units of work called tasks to worker nodes.

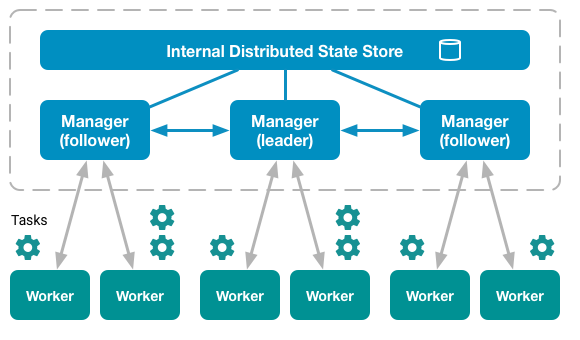

Manager nodes also perform the orchestration and cluster management functions required to maintain the desired state of the swarm. Manager nodes elect a single leader to conduct orchestration tasks.

If you’ve looked at the animation I recommended you’ll know exactly how manager nodes elect a single leader.

8: Oh heck, what’s a Worker Node?

Worker nodes receive and execute tasks dispatched from manager nodes. By default manager nodes are also worker nodes, but you can configure managers to be manager-only nodes. The [worker node] notifies the manager node of the current state of its assigned tasks so the manager can maintain the desired state.

Now we’re getting somewhere. At the heart of Swarm is the notion of a service. This is the core of Swarm and the primary point of user interaction with the swarm. Just like running a container, when you create a service you define which container image to use and which commands to execute inside that container when it runs.

A task is the smallest element of the swarm. It is used to schedule services within the swarm. Managers assign tasks to worker nodes according to the number of replicas defined when the service is created. Once a task has been assigned to a worker node it cannot be moved to another node. It can only run on the assigned node or fail.

Services can be replicated or global. In the replicated model you tell the swarm manager to create and distribute a specific number of replica tasks among the nodes in the cluster. How the manager does this is determined by scheduling strategy you use when you create the swarm.

The diagram below illustrates the structure within a swarm mode cluster:

So, Swarm is a way of creating a lot of copies of a service which maintain the same state and produce the same outcomes and spreading these copies over one or more physical and/or virtual machines in such a way that they appear to the outside world to be a single entity. Phew!

9: Why on earth would we want do this?

The principal reason can be summed up in one word: availability. This has several related meanings in this context:

- It is possible to create a cluster that is distributed over multiple physical regions. By placing the workers carrying out the tasks in closer physical proximity to their clients it is possible to reduce network delays whilst maintaining consistent state between the regions

- If the load increases or decreases significantly in a particular region the scaling capabilities of swarm can be used to create or remove tasks whilst maintaining the desired state. This means that you can add or remove infrastructure in response to real conditions, maximising resource efficiency. In addition, the swarm load-balancer will automatically distribute new tasks between nodes according to the scheme you specify.

- If a particular task fails this will be recognised by the manager and a replacement will automatically be created.

- When deploying updates the swarm manager allows for control of the delay between service deployment to different nodes. If there’s a problem with a deployment it is possible to quickly and easily roll back to a previous version

10: So it that it, then?

Erm… no. This is just the beginning. There are many more reasons for using swarm. In my next few posts I hope to investigate these topics further and to de-mystify the concepts involved. For example, what does it actually mean to maintain a desired state? Come back soon to find out.

Leave a comment