You are a question. What is the answer?

TL,DR;

Creating a start-up is a process of asking questions. What questions you ask, and how you ask them, will depend up the stage you are at in your journey. This post provides a broad outline of the kinds of questions you should be asking yourself and why.

To be or not to be, that is… the result of asking lots of questions

I’d like to propose a definition:

An innovation startup is a business that is testing assumptions that haven’t been tested before (i.e. sufficiently new technologies, product & services and/or markets).

One of the issues that many start-up founders face is that they don’t have a process for approaching innovation. Everything seems unknown. The decisions other, successful, founders make seem to be magical. It’s as though they know something you don’t (funny, that!).

It’s tempting to believe that founding a successful business is simply a talent that some people have that others do not. There may be an element of this, but in reality it is far more a question of process and application than it is of innate ability.

I remember seeing an interview with David Beckham’s coach some time ago. He said that there was nothing intrinsically great about David as a footballer. He wasn’t more talented than everyone else. In fact, when he started he was quite mediocre. What made him the footballer he is was practice. Whenever the coach left the ground at the end of the day Beckham was always there, trying again and again to get it right. Eventually, he got it right!

I believe the same to be true of start-up founders. Knowing what to practice and putting in the hours is what can make the difference between success or failure far more than any natural entrepreneurial ability, in my humble opinion.

To this end, I believe it’s helpful to define the elements of innovation in the following way:

Innovation = Problem x Solution x Execution

For the purposes of this post I’ll be referring to this as the Innovation Equation. That’s very neat, but what does it actually mean?

I believe that there are 3 essential aspects to innovation which are separate but intimately related. The amount of innovation achieved by a start-up is a product of:

- The size of the problem being solved (both in terms of the amount of pain being relieved and the number of people affected by it)

- The amount of benefit provided by the solution to the problem.

- The effectiveness of the execution of that solution.

This is not a scientific definition (the terms amount, size, benefit and effectiveness are in italics because they are somewhat nebulous in their meaning) but is a useful heuristic for defining an approach to achieving successful innovation with a startup:

- First, define the problem to be addressed:

- What exactly is the problem you’re trying to solve?

- Who does it affect?

- Why does it matter?

- Once you have fully defined the problem you can consider what solution you intend to provide:

- What benefits does it bring to the customer?

- How are you testing its potential?

- Why is it better than the alternatives?

- Defining a solution is one thing, making it work is quite another. Execution is arguably the single most important factor in creating a start up, providing that the method of execution supports the problem and the solution:

- How will your idea make money?

- How scalable is your solution in the long term (never worry about scaling in the short term - you need customers before this becomes an issue!)?

- What is your unfair advantage for success?

Questions, questions, questions

If you accept my definition of an innovation startup as stated at the beginning of this post then I hope that what I’m about to say comes as no surprise.

As an innovation startup your very existence is a question

In my work with innovation startups it is usually the case that people understand the general principle described by the equation above:

- Define the problem that is causing customers pain.

- Create a solution that solves it (or part of it).

- Build that solution.

This is not a linear process. In fact, it is usually decidedly non-linear (sometimes even downright messy). It is, however, most definitely a learning process, and if approached correctly it will answer the question that your startup is asking.

The world of any startup is one of uncertainty. This is especially so for innovation startups, which is probably why 9 out of 10 of them fail. The more uncertainty you can mitigate by asking appropriate questions at the right time, the better chance you have of coming up with the right answer.

|

|---|

| Figure 1: Redefining the Build > Measure > Learn cycle |

You may have heard of the Lean Startup principle of Build, Measure, Learn which is designed to support this learning approach. I personally think that this principle could be better stated as:

Experiment > Test > Pivot

The reason I re-state the ‘lean cycle’ like this is that, in it’s original form, I feel that it puts undue emphasis on the Build element of the cycle. I truly believe that words matter, as does the order we say them in. To my mind, the emphasis should be on the question you want to know the answer to and the learning that comes from the answer, not the building itself. Expressing it this way also makes it clear that the point of any experiment is to do something as a result. Experiments are a mechanism to help you decide what to do next.

It’s perfectly OK to have a vision of where you want to get to in 6 months, or 2 years, or whenever. Targets are great motivators. You just need to remember two things;

- To get to that target on the horizon you have to cross all the points in-between

- You must be prepared to change your target if it is becoming obvious that you’re never going to get there.

Targets exist to give us a destination to head for. Experiments exist to test whether we are heading in the right direction. If you set your targets correctly you should be able to place ‘flags in the ground’ between now and the achievement of that target. Use experiments to tell you how far you are deviating from your target, and whether you’re ever likely to get there or whether you should choose another target.

In order to run an experiment you need a hypothesis to test. Your hypotheses should be designed to provide evidence to support the most important assumptions you are making. If those assumptions turn out to be incorrect you need to know now, not when it’s too late.

How do I know what to questions to ask?

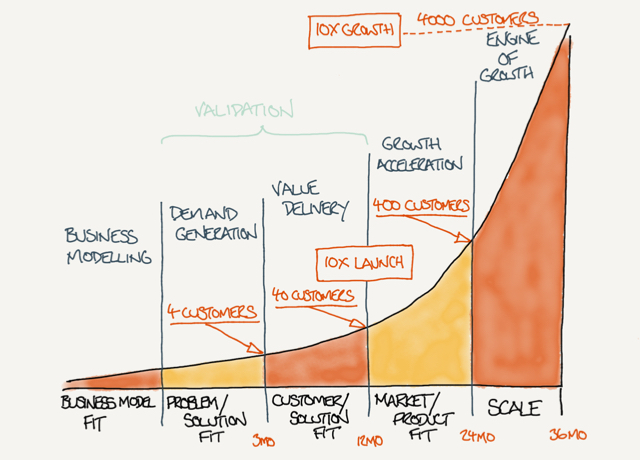

The questions you need to ask will depend upon where you are in the evolution of your business (see Figure 2 below).

|

|---|

| Figure 2: The stages of start-up evolution |

Business Model Fit

In the beginning, you will have a general idea of what you want to do and how you will go about it. The first thing to do when the lightning bolt hits you in the shower, or on your commute into work, or wherever it happens, is to write it down. This way you can share it with at least one other person to check your thinking.

One of the best ways to write down your early business plan is to use a Business Model Canvas (BMC). This is a fast, concise and portable way of describing your proposed business. The BMC deconstructs your business model into 9 distinct sub-parts that can then be systematically tested, in order of highest to lowest risk. As an entrepreneur, your job is not just to build the best solution for your customers but to own the entire business model and make sure all the parts fit.

Problem/Solution Fit

The first real stage in challenging your business model is to determine whether you have a problem worth solving. As you can imagine, it’s far better to find this out before investing months or years of effort and large amounts of money into building a solution.

To help solve this issue it is useful to look at Problem > Solution > Execution in another way. When considering what questions you startup needs to answer I suggest thinking in terms of:

Desirability > Feasibility > Viability

This relates to the innovation equation in the following way:

- Desirability refers to the problem. In essence, you will be asking “Do my customers want/need to have this problem solved?”. Some of the risks that need to be mitigated here are:

- Is the market big enough?

- Will customers pay for it and if so, how much is the solution worth to them?

- Can we reach, acquire and retain target customers?

- Feasibility refers to the solution. The focus here is “Can we do this?”:

- Can the problem be solved?

- The risk is that the business can’t manage, scale or get access to key resources (technology, IP, brand etc.), key activities or key partners.

- Viability can simply be expresses as follows:

- Will customers pay for it?

- Can we generate more revenue than costs?

Customer/Solution Fit

Ask not only ‘how does my customer benefit from this?’ - the user question - but also ‘how are we serving this need better than our competitors?’ - the product question - and ‘how can we show our customers that our product/service is the only logical choice for them?’ - the marketing question.

Market/Product Fit

The key question here is “Have I built something people want?”. Once you’ve found a problem worth solving and you have run enough experiments to create a usable solution your customers can buy you need to test how well your solution solves the problem. You are now trying to measure whether you have built something people want.

Achieving traction is a good indicator that you have achieved market/product fit and is the first significant milestone for your business. As a vague rule of thumb, if you now have 10x more customers than you had on first launch you are on your way to achieving traction.

Growth

Once you have achieved market/product fit you are very likely to have some level of success as a consequence. What you are concerned about now is how to build the customer engine that will require you to scale your business model. Remember, if you are looking for investment then your potential investors are buying into your customer engine, not your product. It is the customer engine that will generate the revenue that justifies their investment.

In order to build your customer engine that results in growth you need to be thinking about the following 5 areas:

- Acquisition - How do I identify and engage with my first users?

- Activation - What is the first value experience these users have that causes them to become customers rather than visitors?

- Retention - What drives repeat usage and keeps reinforcing trust in you and your brand?

- Revenue - What is your pricing model?

- Referral - How do you get existing customers to bring you new customers?

The take-away

If you can change your thinking to recognise the question that your very existence implies and can be honest and rigorous in your responses you have a much better chance of being the 1 company out of 10 that survives and thrives.

Over the next few months I’ll be posting more detail on what sort of questions to ask (and, just as importantly, what questions not to bother asking) and how to ask them depending on the stage you are at and the nature of your startup.

Watch this space!

Leave a comment